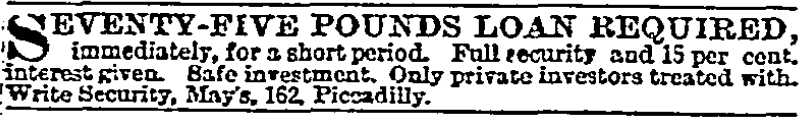

In my most recent blog posts I noted that just before his first and most successful trip to Monte Carlo, Charles Wells placed a small-ad in The Times requesting a loan of £75 “immediately, for a short period”. For this he was prepared to pay an exceptionally generous rate of 15% interest.

Yet several newspapers reported that on the day after the advertisement appeared, Wells was at the Casino and had begun a winning streak which would earn him £20,000 over the next few days – a sum equivalent to about £2 million in today’s value. Would it have been possible for Wells to receive an offer from a lender; collect the money; board a train from London; and arrive in Monte Carlo by the following day, in time to start winning enormous sums at the gaming tables?

Unlikely as it might appear, it is just possible. In Victorian London there were no fewer than twelve postal deliveries every day, beginning at 7.30. A lender could have seen Wells’ advertisement early in the morning and sent off a reply. Wells could have collected the money and proceeded to Victoria Station to catch the daily boat train which left at 11.00. A study of train timetables shows that he would have arrived at Monte Carlo the following day just before 6.00 in the afternoon. This would have left him with about five hours in which to gamble in the casino.

In chapter 17 of my book, The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo, I explain how there may have been more to Wells’ huge wins than first meets the eye, and I show how “the £75 advertisement” may be an important clue to his phenomenal success.