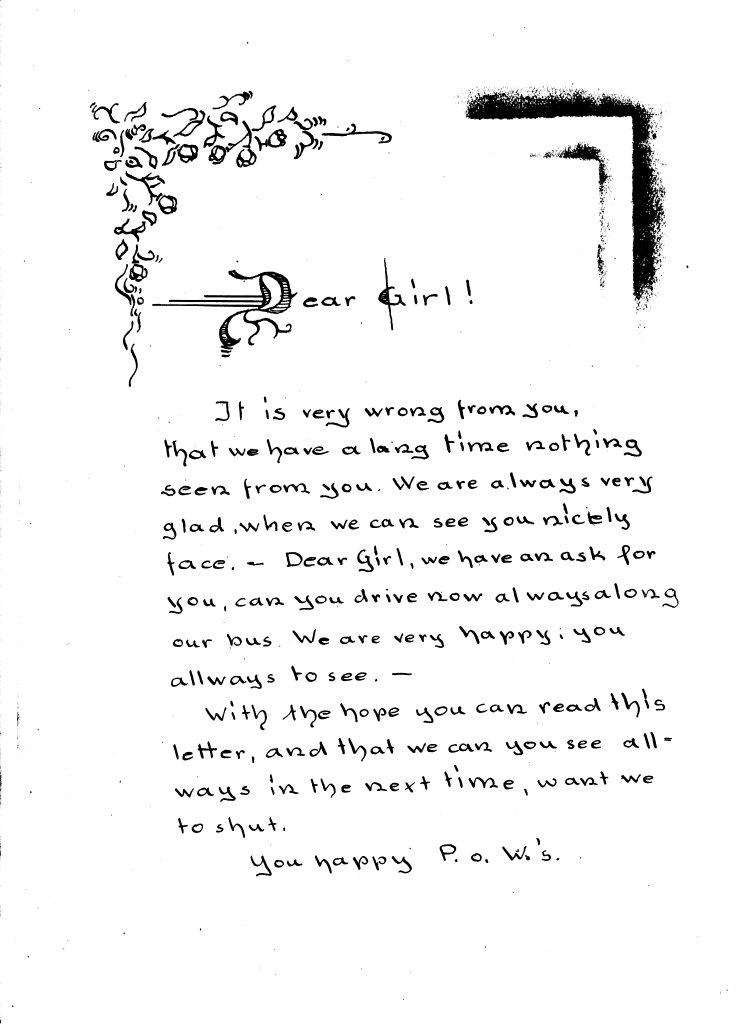

By 1946 some of the Germans had been prisoners for a long period – up to seven years, in some cases – with no immediate prospect of being allowed to return home. ‘We wondered, “How long are we going to be here, how many years?”‘ a former POW reflects. ‘The war had gone on and on and on, then when it was over we were never told when we would be repatriated – whether it would be in a year’s time or two years.’ Finally, in September 1946, Britain began a programme under which at least 15,000 Germans would be returned to their own country every month. But some of the prisoners – particularly those who had lost their families in the war, and those whose homes were now in the eastern zone of Germany – preferred to remain in Britain. ‘I had the chance of going back but the Russians occupied that part of Berlin where my home was,’ one man states. ‘I was talking to my employer’s son, and he said, “You don’t want to go back to Germany under the Russians, you stay here. You can have a job with me as long as you like.” And I wondered what would happen if I went back to the Russian zone of Berlin, and anybody realised I’d been with the Waffen-SS in Russia.’ On learning about the Nazi concentration camps, one man made up his mind that he would not return to Germany. ‘I felt ashamed to be German. I didn’t want anything to do with them – I didn’t want to go home. I couldn’t go to the East and I knew nobody in West Germany. Mum kept writing, “Come home, come home,” but I thought “Never!”‘ [From Hitler’s Last Army, chapters 8 and 19]