As a young man, Charles Deville Wells had practised as an engineer in France, and had invented an apparatus for regulating the speed of ships’ propellers. He sold the patent to a steamship company for 5,000 francs – a very large sum at the time.

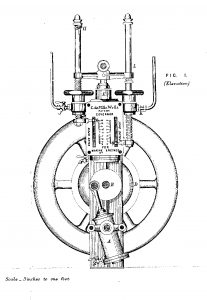

A diagram showing the device for regulating the speed of ships’ propellers. This image formed part of Wells’ patent application of 1868.

Some twenty years later he used his earlier engineering expertise to set up a scam, in which he persuaded well-heeled investors to sponsor another invention of his. This piece of equipment, he assured them, would greatly increase the fuel-efficiency of steam engines. Considering that steam power was the mainstay of transport and industry around the world, any effective method of saving coal would indeed have been worth a fortune. Wells told his would-be financiers that the gadget could provide savings of 50%, and promised to share the proceeds if they backed his idea.

The really clever part of his scheme is that what he claimed must have been totally believable at that time – especially to a lay person. I recently watched the repeat of a BBC documentary, Why the Industrial Revolution Happened Here. This shows how the earliest steam engines had an efficiency of only 5%. By the late 1880s to early 1990s, when Wells was operating his scam, newer designs of engines had achieved a figure of 10%. Thus it was clear not only that efficiency could be doubled, but that there was still more than ample room for further improvement. Two of his investors handed over sums approaching £3 million in today’s money, but never received a penny of the promised profits.

In fact, steam power never achieved much more than 10% efficiency: and at the time when Wells was peddling his device, the internal combustion engine was already being developed. As we now know, this would make the steam engine virtually redundant – though it would take more than half a century to do so.