Charles Deville Wells, the Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo

A few weeks ago I ran a “mini-series” of blog posts, featuring some of Charles Wells’ partners in crime. The name of Henry Baker Vaughan came to mind at the time, but I hesitated to include him as one of Wells’ side-kicks because, I believe, he was only a reluctant accomplice. But his story is an interesting one, so I’ve decided to add him to the list as an afterthought.

Henry Baker Vaughan was born in about 1858 and – in common with thousands of others in those days before typewriters, photocopiers and word-processing – he became a legal clerk. We can almost picture him as he stands at a tall desk like a preacher’s pulpit, scratching away with a quill pen like a character out of Dickens.

He married Mary Anne Barber in 1881 and they set about producing a large brood of children. Life must have been hard for a young man with such a large family working at a job which was notoriously badly paid. One day in about 1887, though, he spotted an advertisement in the paper. A businessman was seeking a legal clerk.

Vaughan went along to meet this entrepreneur, who turned out to be Charles Deville Wells. Wells took him on, promising to pay him 12s 6d (equivalent to about £60 today) to copy by hand 500 letters relating to patents for which he was seeking financial backing. This must have been a dreadfully repetitive and mind-numbing task, but Vaughan duly delivered the letters to Wells, who elected to pay him only 7s 6d (worth just under £40 today), instead of the amount he had promised. Vaughan was hardly in a position to argue, and over a period of a few years he made some 3,000 copies like these.

(Lest there be any doubt, the inventions that Wells claimed to have patented were all phony, and few, if any, of the investors ever got any money back).

Up to now, of course, Vaughan himself had done nothing wrong and was probably unaware that Wells was operating a scam. But soon the young clerk, always strapped for cash, and with an ever-expanding family, was tempted to depart from the straight and narrow. At the same time as he was employed by Charles Wells, Vaughan also did some work for a legal firm. He once mentioned to Wells that he was going to Temple Chambers and Wells asked him to write a letter from there about an agreement between himself and a client. Wells offered him £1 (equivalent to £100 today) if he would write a “legal opinion” stating that the contract was a fair one.

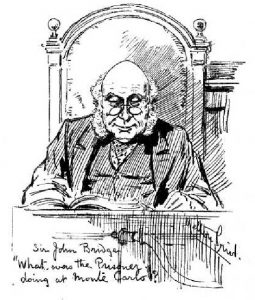

Sir John Bridge, Chief Magistrate for London

Charles Deville Wells – the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo – in the dock at Bow Street Magistrates Court prior to being sent for trial at the Old Bailey.

Some time later, when Wells went on trial at the Old Bailey for fraud, Vaughan was a prosecution witness. He testified that Wells had asked him to accompany him to Paris in connection with a company that Wells was forming. (Naturally, this undertaking was later discovered to be a sham). While they were in the French capital, Wells gave him an Affidavit to copy out. Among other details the document named Vaughan as Company Secretary, and after he had made a copy they went together to the British Consulate where Vaughan swore the Affidavit.

After Vaughan had recited this saga in court, the judge remarked, ‘You need not answer any questions that may prejudice yourself.’ The hapless clerk seems to have been shaken by this comment. Up to now Vaughan had not felt that he had done anything wrong, but now the judge seemed to imply that he had participated in a deception on a huge scale.

He blurted out, ‘I have nothing to conceal that I am aware of.’

In the event, no further action was taken against Vaughan, but his career seems to have been tainted by his association with Wells, and it is evident that he had difficulty finding further work within the legal sector. The 1901 census finds him and his wife living in Greenwich accompanied by no fewer than nine sons and daughters ranging from 1 to 18 years of age. Vaughan is now working as a dock labourer.

Henry Baker Vaughan’s story ends with a particularly sad twist. It seems that even 15 years after working for Wells he was still regarded with a certain amount of suspicion. Shortly before Christmas 1906, these few lines appeared in a newspaper:

PATHETIC STORY OF DESPAIR

Mr. N. Schroder held an inquest at Hampstead on Henry Baker Vaughan, aged 49 years, lately living in Woodstock Road, Walthamstow, who committed suicide by taking arsenic on Hampstead Heath. Herbert Rowe, manager to George May, a Fulham moneylender, in whose service deceased was, stated that the latter told him that he recently lost £3 through a hole in his pocket, and had to make it good, and was suspended pending examination of the accounts, and he was much depressed. The books were [subsequently] found quite correct. — A verdict of Suicide during temporary insanity was returned.

A number of sources were consulted in piecing together Vaughan’s story. For his court appearance I relied in particular on the account in The London Evening Standard of 16 February 1893. His death was reported in the Essex Newsman of 8 December 1906, and other publications. Both papers can be consulted online at www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk