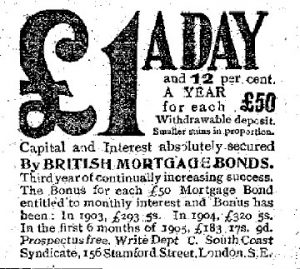

Wells and Moyle placed this advertisement in a number of provincial and national newspapers. This example is from the Daily Mirror of 17 July, 1905.

In 1905 two men were imprisoned for selling shares in a bogus company – the improbably-named South and South-West Coast Steam Trawling and Fishing Syndicate. They had promised would-be investors that all funds would be fully secured against a ‘first-class vessel’, the Shanklin. In fact this boat was worthless. It had not left its berth for many a month, and had sunk at its moorings on the River Mersey.

Victims of the scam included a high-ranking official of the City of London, and a Viscount with connections to the royal family. Even so, the case attracted only slight media attention at first; scams of this kind were not at all uncommon. But a media frenzy erupted when it was revealed that one of the fraudsters, who went under the name “William Davenport” was in fact none other than Charles Deville Wells – better known as “Monte Carlo Wells”, the man who had broken the bank at Monte Carlo some 14 years previously.

His accomplice was the Reverend Vyvyan Henry Moyle – a clergyman with a most unusual background. Some 40 years earlier he had been appointed vicar of a Yorkshire parish. It quickly became apparent that Moyle had begun to enjoy an unusually high standard of living for a clergyman. One visitor was amazed when Moyle sent a smart carriage and a liveried footman to meet him at the station. To account for his lavish lifestyle, Moyle hinted that he had come into a substantial inheritance. In fact the reason for his new-found wealth was that he had forged a substantial number of share certificates and netted the present-day equivalent of around £1.7 million. After serving a 7-year prison sentence he had been pardoned by his superiors and allowed to continue as a priest. Then, around 1904, he had met “Davenport” and between them they had cooked up another fraudulent scheme.

However, investors began to have doubts about the two smooth-talking confidence tricksters. When police finally arrested Moyle on a charge of conspiring to obtain money by fraud, he immediately tried to shift all the blame on to Wells: ‘I haven’t conspired with anyone,’ he protested. ‘I don’t know what Davenport has done. Why don’t you arrest him? He’s the head of the concern.’

At their trial the judge remarked that Moyle was not the originator of the scheme and was to be imprisoned for eighteen months. Wells – ‘a man of very considerable ability’, according to the judge – was sentenced to three years penal servitude, a relatively light punishment, in the hope that he would reform when he came out of prison.

As readers may by now have guessed, Wells certainly did not reform when he came out of prison. In fact, his most spectacular crime of all was yet to come. If this affair was to teach him anything at all it was that there is no honour among thieves, and in future he would work alone. There would be no more accomplices – except for the love of his life, his long-term mistress, Jeannette Pairis.

(From The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo – Charles Wells, gambler and fraudster extraordinaire by Robin Quinn).

Jeannette Pairis, pictured around 1891 when her lover, Charles Wells broke the bank at Monte Carlo. (The National Archives)