CHARLES DEVILLE WELLS ARRIVES IN MONTE CARLO

When Charles Wells placed an advertisement in The Times for a £75 loan (see yesterday’s post), he was presumably hoping that 80 people would respond with an offer. This would have given him the £6,000 he deemed necessary for his ‘infallible gambling system’ to work as intended. But immediately after placing the ad, he somehow obtained from other sources £4,000 – equivalent to £400,000 today. Gambling with a smaller amount of capital was a risky move. But he evidently thought it was worth taking a chance: and by the time his appeal for funds appeared in print he was already his way to Monte Carlo.

The casino at Monte Carlo. One night in 1891 Charles Wells crossed the square (right foreground) to his hotel, staggering under the weight of a million francs in banknotes and slept with them under his pillow.

As Wells takes his seat the croupiers eye him with the silent disdain of a waiter who spots a customer using the wrong fork. The game of roulette begins, and the croupier says in an expressionless voice, ‘Faites vos jeux, messieurs — Place your bets, gentlemen’. (Women may play, but their presence is never acknowledged by the croupier).

Charles takes several louis – small gold coins worth 20 f – and places them carefully on the numbered squares marked on the green baize of the roulette table. Chips are not used: all bets must be made in cash – either gold louis or banknotes. [At the time, tokens – or ‘chips’ – had been tried experimentally, but it was found that they were too easy to counterfeit. By the time of Wells’ visit, the Casino had gone back to using cash only. Today, each gambler is issued with chips of a different colour or pattern to help the croupier to distinguish where each player has placed his or her stake.]

The croupier reaches for the handle at the centre of the roulette wheel and, with a little flourish, gives it a spin. He takes the small, white ivory ball and expertly throws it in the opposite direction to that of the wheel – or cylindre, as the croupiers always call it. The wheel begins, almost imperceptibly, to slow. In a firm voice the croupier says, ‘Les jeux sont faits — The bets have been placed’. And, as if responding to his words, the white ball begins its downward spiral. ‘Rien ne va plus — No more bets will be accepted’. With a faint rattling sound the ball meshes with the wheel, finally settling into one of the numbered pockets. The whole cycle takes about sixty seconds, and will be repeated over and over again by the time the casino closes late that night.

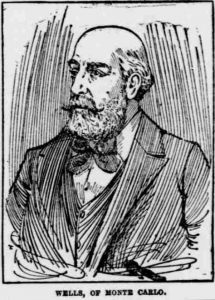

THE MAN WHO BROKE THE BANK AT MONTE CARLO : Charles Deville Wells, gambler and fraudster extraordinaire. A newspaper illustration from the 1890s

People seemed to appear from nowhere. The Casino – empty a short time earlier – was suddenly teeming with humanity. With a murmur here, a whisper there – finally an outbreak of animated chatter, a crowd formed around Wells’ table to observe this unassuming little man with the bald head and dark moustache and beard.

The seats around the table, beside and opposite Wells, were all occupied now. Standing behind them, sometimes on tip-toe, sometimes squeezing forward for a better view, a crowd of onlookers grew steadily. From the back it was hard to see what was going on and even harder to participate in the play: and so the spectators jostled and shoved one another in an undignified melée as they tried to get closer.

… By eleven o’clock in the evening – closing time at the Casino – Charles Wells had broken the bank. In one day he had transformed the £4,000 he had brought with him into £10,000 [£1 million]. He left with his winnings, felt the cool breeze on his face and breathed in the evening air, laden with the scent of the fragrant plants in the casino gardens – a welcome change from the stuffy, ill-ventilated gaming halls.

The above excerpts are from The Man who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo – Charles Deville Wells, Gambler and Fraudster Extraordinaire by Robin Quinn